Singapore’s food scene is a story shaped by oceans, empires, and centuries-old trade. As a photographer focused on our culinary traditions, I find inspiration not only at bustling markets and hawker centres, but in the layered history written across every dish. Singapore was once a vibrant port, a meeting point of cultures from China, India, and Europe. This melting pot set the foundation for Singapore colonial food history—an ever-evolving fusion cuisine that remains at the heart of our nation’s identity.

Black Pepper

The quest for spices like black pepper, cinnamon, and cumin led Portuguese explorers, such as Vasco da Gama, into Southeast Asia. Black pepper quickly became an emblem of cross-continental flavor, influencing food from simple street stalls to celebratory banquets. As Portuguese and later Dutch, British, Indian, and Chinese traders settled—or passed through—Singapore, black pepper and other spices turned local kitchens into laboratories of cultural exchange. These influences paved the way for what would later define Eurasian cuisine.

Culinary Traditions

At the core of this legacy is the vibrant world of Eurasian food. Through centuries of mingling between Europeans—especially Portuguese, Dutch, and British—and local Malay and Chinese communities, new culinary traditions took root. These were stories told through recipes: techniques borrowed, ingredients shared, methods blended. Each dish preserves generations of adaptation and cross-pollination, making Eurasian cuisine a living representation of Singapore’s layered history.

Devil's Curry

My personal connection with this culinary fusion was sealed with my first taste of Devil’s Curry. Known locally as Curry Debal, this dish is a bold, unabashed stew. Southeast Asian spices—turmeric, galangal, black pepper—meld with the sharp tang of vinegar, a nod to European preservation. Cooked traditionally with leftover meats and sausages from festive roasts, Devil’s Curry is a celebration of resilience and creative adaptation. It’s often prepared in large batches for big family gatherings, with every bowl telling a story of survival, community, and joy through hardship.

Macanese Cuisine

Singapore’s food evolution didn’t happen in isolation. As Portuguese traders and migrants continued through Southeast Asia, their cooking traditions merged with those in Macau, creating Macanese cuisine. Dishes like African Chicken—blending coconut milk, paprika, and a melange of spices—capture the journey of recipes across continents. These savory stews and grilled meats arrived in Singapore, their flavors further deepened by Southeast Asian spices and local twists. Meals became passports, connecting Singapore to distant Malacca, Macau, India, and Portugal.

Sugee Cake

A Eurasian celebration is never complete without sugee cake. Made from semolina flour, butter, and ground almonds, this cake is soft, rich, and deeply aromatic. Adapted from European cake-making traditions, it uses regional ingredients like coconut and ghee. Served at weddings, birthdays, or festive holidays, sugee cake embodies the sweet side of the Eurasian story, offering a bite-sized history lesson with every piece.

Eurasian Restaurant

To truly experience Singapore’s Eurasian culinary legacy, a visit to a Eurasian restaurant is essential. Quentin’s Eurasian Restaurant, with locations at the Eurasian Community House and Changi Business Park, is one such torchbearer. Helmed by executive chef Quentin Pereira, their kitchen is known for heritage classics—Devil’s Curry, Prawn Bostador, Sugee Cake—each meticulously prepared using time-honored recipes. These restaurants are more than just places to eat; they are testing grounds and preservers of culinary heritage, sustaining the spirit of the Eurasian community for future generations.

Culinary Legacy

The legacy of Singapore colonial food history lives on—transcending boundaries, reimagined by families and chefs alike. Each rich stew, buttery dessert, and spicy curry is a tribute to the harmonious blend of cultures that shaped them. The Eurasian cuisine we savor in Singapore now is not simply a relic; it is a breathing, growing part of our shared narrative.

Today, as culinary boundaries blur across the world, Singapore’s fusion food stands as powerful proof of possibility. Devil’s Curry, sugee cake, and Macanese-inspired African Chicken are more than delicious—they’re postcards from the past, celebrating centuries of global trade, cultural exchange, and resilience. From bustling markets to the family table, these dishes weave together the stories of people, places, and tastes that make Singapore a true crossroads of the world. This is the heritage I strive to capture, one flavor and one photograph at a time.

To explore another iconic dish from Singapore's rich culinary history, check out how the traditional poaching technique brings Hainanese Chicken Rice to life in this fascinating exploration of heritage cooking.

Composition’s Sweet Spot: A Guide in Framing Desire for Food Bloggers in Singapore

January 30, 2026

You have found the perfect bowl of bak chor mee. The noodles glisten, the minced pork is perfectly seasoned, and the chili sauce adds a vibrant splash of red. You snap a quick picture, but…

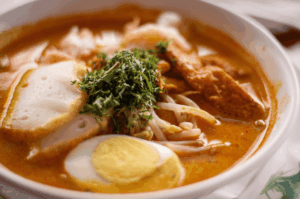

Laksa’s Velvet Embrace Welcomes the Best Foodies

January 26, 2026

There are dishes that you eat, and then there are dishes that you experience. Laksa is firmly in the latter category. It is an intoxicating, full-body immersion into a world of flavor, a dish so…

Tiong Bahru: The Slow Seduction of Food in Photography

January 23, 2026

Some neighborhoods shout for your attention. They are a riot of sound, color, and frantic energy. Tiong Bahru is not one of them. This corner of Singapore operates on a different frequency, a slower and…

Chili Crab Confidential: Producing Perfect Pics of Food

January 19, 2026

It arrives like royalty, carried to the table with a sense of occasion. A colossal crab, bathed in a thick, shimmering sauce the color of a fiery sunset. The air around it is fragrant with…

The Art of the Tease: Captured in Food Photography

January 16, 2026

In the world of food photography, there is a powerful and often overlooked technique, a subtle language of visual seduction. It is the art of the tease. It is the practice of not showing everything,…

Geylang’s Secret Appetites: A Guide for Every SG Foodie

January 12, 2026

There is a side of Singapore that hums with a different energy. It is a place where the polished gleam of the city gives way to a raw, vibrant, and unapologetic reality. This is Geylang….

The Peranakan Seduction: A Food Photography Photographer’s Insight

January 11, 2026

There are some cuisines that you photograph, and there are some that you court. Peranakan food falls firmly into the latter category. It is a seduction of the senses, a rich tapestry of history, flavor,…

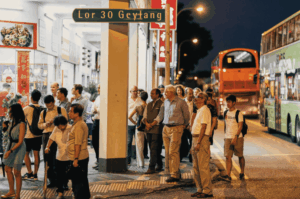

Geylang’s Forbidden Flavors: The Best Foodies District

January 9, 2026

Mention Geylang, and you will likely get a mix of reactions. This neighborhood, with its gritty reputation and neon-lit side streets, exists in a space separate from Singapore’s polished image. But for those in the…

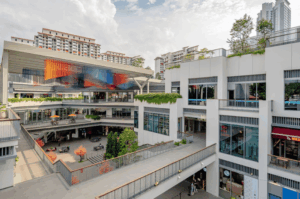

Holland Village: East Meets West Journey of Food and Photography

January 2, 2026

There is a corner of Singapore where the laid-back charm of a European village collides with the vibrant energy of a Southeast Asian city. It is a place where the aroma of freshly brewed espresso…

The Tease of Motion: Capturing Culinary Food in Photography

December 29, 2025

Food is rarely static. It drips, sizzles, steams, and crumbles. It is poured, flipped, chopped, and shared. Yet, so often, we see food in photography presented as a perfectly still, lifeless object on a plate….